/ Nov 05, 2025

Trending

Vanessa Ferreira, ND

Verruca vulgaris, typically referred to as common warts, is one of the most prevalent benign skin neoplasms among children and adolescents. In some countries, up to one-third of school-age children suffer from common warts, and up to 20% seek professional medical treatment.1 Although the lesions are benign, they can become painful and unsightly and are a common complaint among patients visiting dermatologists.2 There are numerous treatments for verruca vulgaris, but no single treatment has been established as completely curative.3 Treatments range from topical salicylic acid, dermatologist-guided cryotherapy, and – for more serious conditions – surgical excision under general anesthesia. This case report presents a patient afflicted with severe and persistent warts who found therapeutic benefit using a commercially available botanical formulation.

Verruca vulgaris begins as a viral infection of the skin. The human papilloma virus (HPV) is a double-stranded, circular, supercoiled DNA virus that has been identified as the agent responsible for the formation of warts. There are more than 100 genotypes of HPV. HPV-2 and HPV-4 are the most common genotypes associated with verruca vulgaris; other genotypes include HPV-1, HPV-3, HPV-27, and HPV-57. HPV can frequently be isolated on the skin of healthy individuals, but is usually asymptomatic. Samples taken from subjects showed a prevalence of asymptomatic HPV infection in 80% of healthy individuals.1 The most prevalent genotypes of HPV found in these asymptomatic cases are HPV-1 (59%), HPV-2 (42%), HPV-63 (25%) and HPV-27 (21%).1 It is believed that the most causative factors for developing warts are the use of communal showers, meat-handling, and immune incompetence.3 Beyond common warts, there are 15 HPV genotypes that are associated with high risk for the development of cervical oncogenic lesions, with HPV-16, HPV-18 and HPV-45 being the most prevalent.4 When HPV infects the epithelial cell layer, it produces the viral E6 and E7 proteins. These proteins have been characterized as suppressors of the cellular p53 and retinoblastoma gene products.5 The outcome of this attack on the host cell is to promote growth, resulting in the formation of benign warts or oncogenic lesions.5

Salicylic acid is often the first line of treatment for verruca vulgaris. However, salicylic acid is not optimal, since it is a slow-acting treatment and requires frequent application. Salicylic acid works by “peeling the skin” and removing the virally-infected epithelial cells. The procedure is often well tolerated, but it can result in burns and other complications.6 Cryotherapy using liquid nitrogen is commonly used as well, but it is only efficacious approximately 50% of the time, even after multiple treatments.3 In addition, it is moderately invasive and painful to the patient. The treatment involves freezing the wart to destroy HPV-infected cells. Every layer of affected skin must be treated for the cryotherapy to be successful; however, it is often difficult to assess the depth of the cryotherapy application.7 Other standard treatments include intralesional injections, systemic agents, laser electrodessication, surgical excision,2 and other topical agents, such as cantharidin.3 Cantharidin is a compound that works by inducing cell death through the inhibition of heat shock proteins and the promotion of spontaneous apoptosis.8

It has been reported in the literature that certain plant compounds can inhibit virus replication.9 In the case presented here, the patient had previously received some of these first-line treatments, but without successful resolution of her warts. The patient presented with a chronic and severe case of verruca vulgaris, and she was subsequently treated with a topically applied botanical formulation. Within a month’s time of treatment, the patient’s warts were nearly resolved, demonstrating the efficacy of the botanical blend.

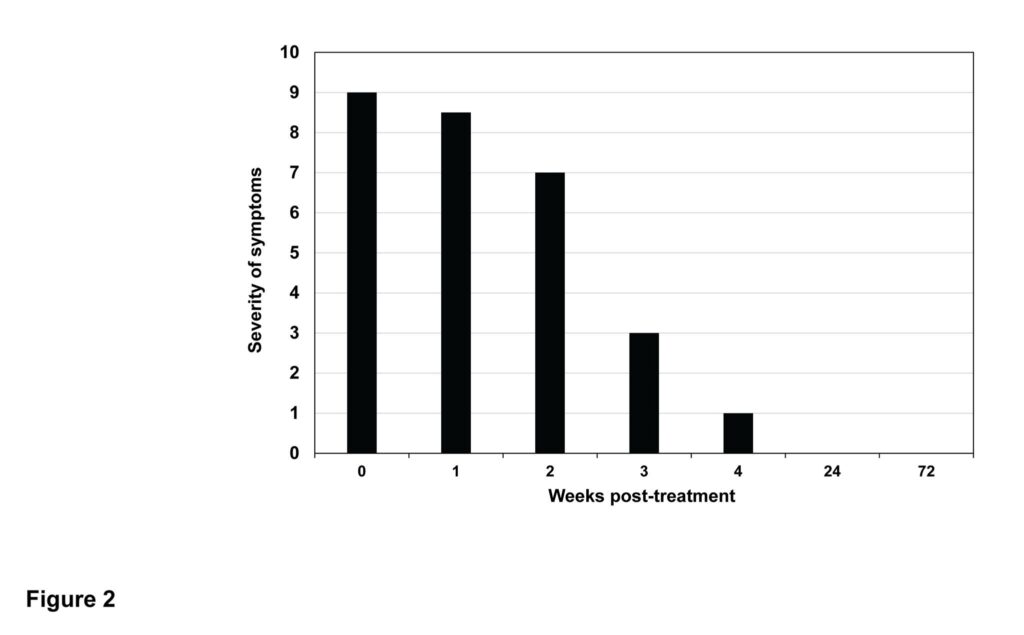

A 21-year-old female patient presented with a diagnosis of verruca vulgaris (common warts), with visible elevated and roughened lesions on the palm of the right hand. Photographs of the patient’s lesions were obtained upon initial intake (pretreatment), 3 weeks into treatment, 4 weeks into treatment, and 6 months following treatment. All images represent the palm of the right hand.

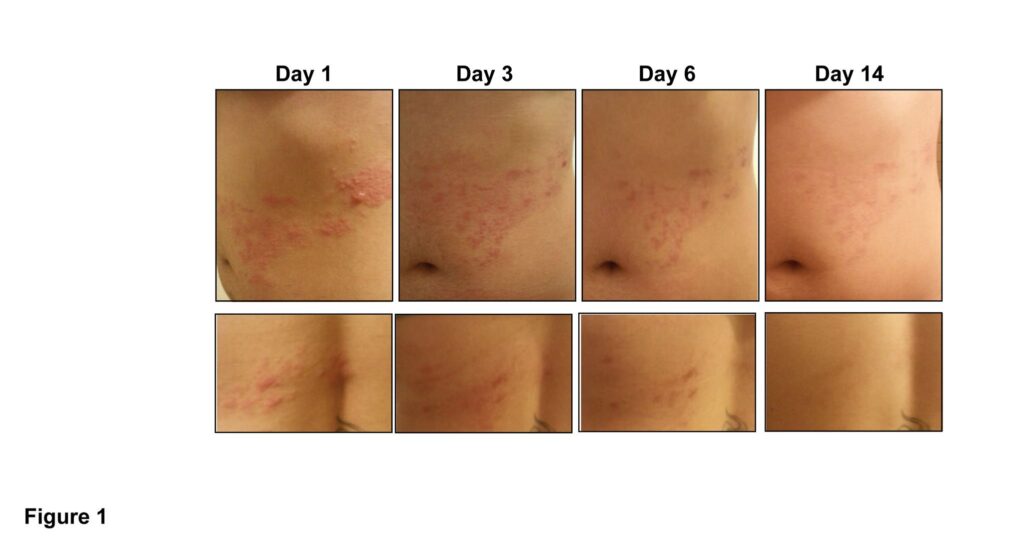

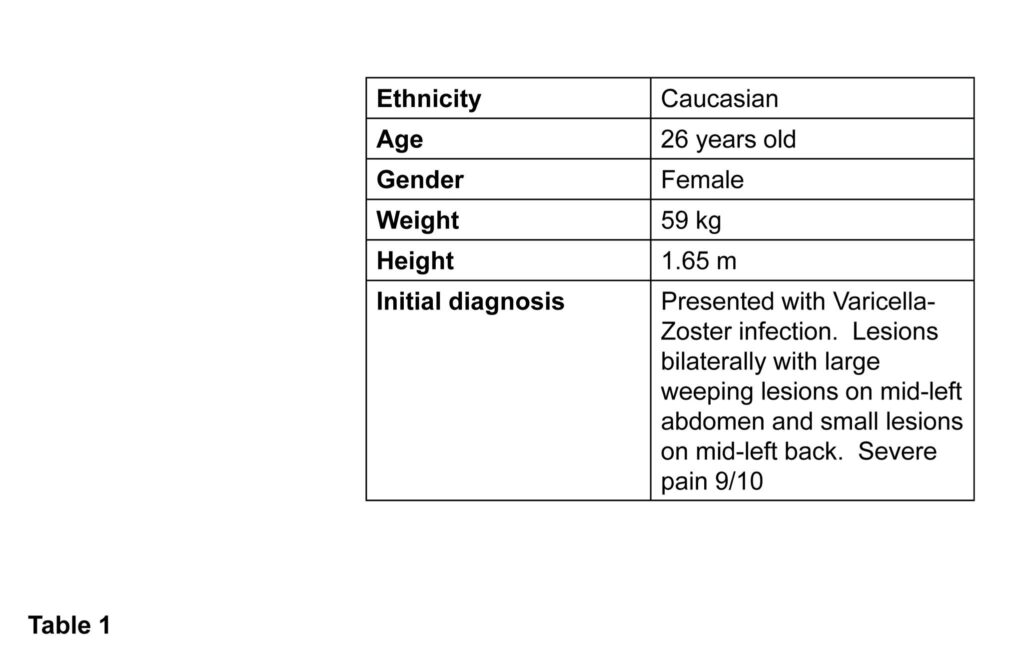

Before treatment, multiple lesions of various size covered approximately 20% of the patient’s palm (Figure 1). The largest lesion was 3.2 cm in length. The patient’s physical characteristics at intake are shown in Table 1.

The patient reported having the warts for 12-14 months. Prior to intake at our facility, she had received treatment from a dermatologist. This treatment involved cryotherapy with liquid nitrogen. It was unsuccessful and the warts returned. Subsequently, the patient was treated with cantharidin. This treatment resulted in the development of severe blisters and was a very painful experience for the patient. Following this treatment, the warts returned without any resolution of symptoms. The patient was subsequently scheduled for surgical excision of the warts. Not wanting to undertake the surgical procedure, she contacted our facility. The cantharidin treatment had occurred 2 months prior to our initial intake of the patient.

Upon intake, the patient had complaints of pain, erythema, and disfigurement to the right palm, coupled with the psychological stigma associated with the warts. The patient’s vital signs and medical history were taken, which did not affect the diagnosis or treatment plan. After a medically focused assessment, a botanical-based therapy was implemented. Many botanicals have proven antiviral and analgesic properties. A commercially available botanical gel containing Hypericum perforatum (2.5%), Lavandula officinalis (10%), Glycyrrhiza glabra (2.5%), Melissa officinalis at (6%), Eleutherococcus senticosus (4%), and Sarracenia (mixed species) (25%), suspended in a proprietary gel, was chosen due to the historical antiviral and analgesic properties associated with these botanicals. In addition, the gel formulation contained allantoin and glycerin, which are known to improve skin healing.10,11

Explicit instructions were given to the patient, including detailed application instructions. These included: a) wash the area with warm water only (no soap) and pat dry; b) beginning at the outer edge of the area, apply a very thin layer of the gel, then apply the gel to all remaining lesions uniformly; and c) cover the entire area with a Teflon-coated bandage. Reapply the gel QID, rewashing the area prior to bedtime and once again in the morning. Repeat the instructions for each application. The patient was asked to document any side effects or concerns.

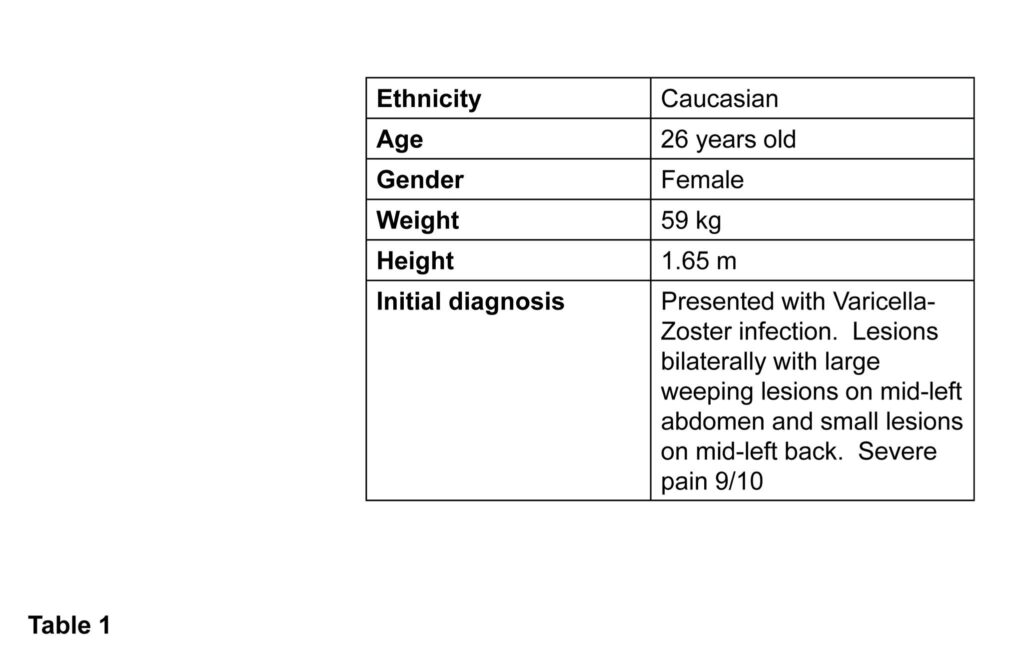

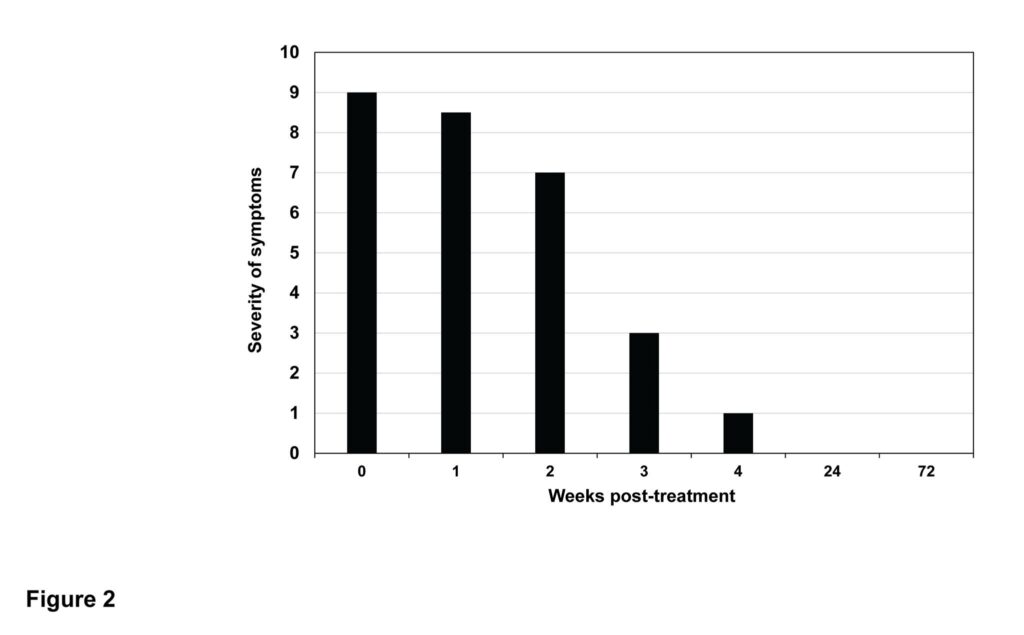

After the first 2 weeks of treatment, the patient reported minor changes in symptoms, including a slight increase in redness surrounding the lesions (Figure 2). The patient reported an absence of any pain associated with the lesions within the first day after application of the gel.

Figure 2. Severity of Symptoms Over Time

Symptoms were ranked on a scale of 0-10 (10 being most severe). Assessed symptoms included the diameter and elevation of lesions, erythema, and pain. Symptoms were recorded during the initial intake, weekly visits, and follow-up visits.

During the third week of treatment, the roughness and elevation of the lesions were greatly diminished (Figure 2), but they remained erythematous (Figure 1).

At the 4-week mark, the lesions were substantially healed and were “leathery” in appearance (Figure 1). The erythema of the lesions diminished and appeared slightly pink in color. The patient reported no pain or any side effects during the entire treatment period. At this point it was decided to discontinue the use of the gel and proceed to monitor the patient for any reoccurrence.

At the patient’s 6-month follow-up, no warts or erythema was observed (Figure 1). At an 18-month follow-up, the patient remained asymptomatic.

This case supports the use of a topically applied botanical formulation as an efficacious and non-invasive treatment for verruca vulgaris. The botanical gel was selected due to the antiviral and analgesic properties historically associated with the ingredients. The botanicals present in the blend included Hypericum perforatum, Lavandula officinalis, Glycyrrhiza glabra, Melissa officinalis, Eleutherococcus senticosus and Sarracenia spp suspended in a gel. Hypericum perforatum has been shown in vitro to inhibit the transcription of the hepatitis B virus.12 Melissa officinalis has demonstrated inhibitory properties against herpes simplex viruses,13 and Glycyrrhiza glabra has shown in mouse models to have activity against the papilloma virus.14 The root of Eleutherococcus senticosus has shown antiviral activity against DNA viruses, including adenovirus and herpes simplex virus-1.15 Historically and in laboratory studies, Sarracenia purpurea has demonstrated activity against poxviruses.16

All of these aforementioned viruses have a similar feature of a DNA-based genome. Although none of these botanicals have substantial historical activity against HPV, the DNA genome structure of HPV may suggest the use of these botanicals against this virus family as well. In addition, the botanical Sarracenia has a long history of pain relief, as it has been used for centuries as an anesthetic17 and is currently marketed as a pharmaceutical analgesic.18 For the case presented here, the botanical formulation provided relief of symptoms, likely through the antiviral and analgesic properties associated with these botanicals.19

Current standard treatments of care for verruca vulgaris are commonly invasive, painful, and often unsuccessful.20 The use of this synergistic blend of botanicals in a gel base could prove to be a more efficacious treatment than the current standard of care. Current literature supports the use of traditional medicinal herbs in the treatment of viral infections.21 The efficacy observed in this case study supports the need for additional research of this botanical formulation, not only against HPV strains associated with common warts, but also for more severe HPV strains, including HPV-6 and 11, and HPV-16 and 18, which lead to genital warts and cervical cancer, respectively. Further investigation into novel uses of botanical extracts, as well as their polypharmaceutical interactions, should be encouraged21 in order to provide patients with efficacious and non-invasive alternatives to current HPV treatments.

Vanessa Ferreira, ND, is a naturopathic physician from SCNM, where she completed this case study as a student. During her naturopathic education, Dr Ferreira focused her time on Global Health, Women’s Health, and Homeopathy. In addition, she has extensive experience as a teaching and research assistant at SCNM. Her main research project – on inhibiting Candida growth and differentiation with the use of botanicals – was showcased at the AANP in 2014. Dr Ferreira has worked in the Biodesign Institute at Arizona State University, doing research on botanicals and herpes viruses. She looks forward to providing more case-based research to support the efficacy of modalities used in naturopathic medicine in the future.

Vanessa Ferreira, ND, is a naturopathic physician from SCNM, where she completed this case study as a student. During her naturopathic education, Dr Ferreira focused her time on Global Health, Women’s Health, and Homeopathy. In addition, she has extensive experience as a teaching and research assistant at SCNM. Her main research project – on inhibiting Candida growth and differentiation with the use of botanicals – was showcased at the AANP in 2014. Dr Ferreira has worked in the Biodesign Institute at Arizona State University, doing research on botanicals and herpes viruses. She looks forward to providing more case-based research to support the efficacy of modalities used in naturopathic medicine in the future.

Author Affiliations:

1Southwest College of Naturopathic Medicine, Tempe, AZ 85282; 2Arizona State University, Biodesign Institute, Tempe, AZ 85287; 3Precision Surgical, LLC, Scottsdale, AZ 85260; 4Total Wellness Medical Center/Vital Force Naturopathic Compounding, Surprise, AZ 85374

References

Vanessa Ferreira, ND

Verruca vulgaris, typically referred to as common warts, is one of the most prevalent benign skin neoplasms among children and adolescents. In some countries, up to one-third of school-age children suffer from common warts, and up to 20% seek professional medical treatment.1 Although the lesions are benign, they can become painful and unsightly and are a common complaint among patients visiting dermatologists.2 There are numerous treatments for verruca vulgaris, but no single treatment has been established as completely curative.3 Treatments range from topical salicylic acid, dermatologist-guided cryotherapy, and – for more serious conditions – surgical excision under general anesthesia. This case report presents a patient afflicted with severe and persistent warts who found therapeutic benefit using a commercially available botanical formulation.

Verruca vulgaris begins as a viral infection of the skin. The human papilloma virus (HPV) is a double-stranded, circular, supercoiled DNA virus that has been identified as the agent responsible for the formation of warts. There are more than 100 genotypes of HPV. HPV-2 and HPV-4 are the most common genotypes associated with verruca vulgaris; other genotypes include HPV-1, HPV-3, HPV-27, and HPV-57. HPV can frequently be isolated on the skin of healthy individuals, but is usually asymptomatic. Samples taken from subjects showed a prevalence of asymptomatic HPV infection in 80% of healthy individuals.1 The most prevalent genotypes of HPV found in these asymptomatic cases are HPV-1 (59%), HPV-2 (42%), HPV-63 (25%) and HPV-27 (21%).1 It is believed that the most causative factors for developing warts are the use of communal showers, meat-handling, and immune incompetence.3 Beyond common warts, there are 15 HPV genotypes that are associated with high risk for the development of cervical oncogenic lesions, with HPV-16, HPV-18 and HPV-45 being the most prevalent.4 When HPV infects the epithelial cell layer, it produces the viral E6 and E7 proteins. These proteins have been characterized as suppressors of the cellular p53 and retinoblastoma gene products.5 The outcome of this attack on the host cell is to promote growth, resulting in the formation of benign warts or oncogenic lesions.5

Salicylic acid is often the first line of treatment for verruca vulgaris. However, salicylic acid is not optimal, since it is a slow-acting treatment and requires frequent application. Salicylic acid works by “peeling the skin” and removing the virally-infected epithelial cells. The procedure is often well tolerated, but it can result in burns and other complications.6 Cryotherapy using liquid nitrogen is commonly used as well, but it is only efficacious approximately 50% of the time, even after multiple treatments.3 In addition, it is moderately invasive and painful to the patient. The treatment involves freezing the wart to destroy HPV-infected cells. Every layer of affected skin must be treated for the cryotherapy to be successful; however, it is often difficult to assess the depth of the cryotherapy application.7 Other standard treatments include intralesional injections, systemic agents, laser electrodessication, surgical excision,2 and other topical agents, such as cantharidin.3 Cantharidin is a compound that works by inducing cell death through the inhibition of heat shock proteins and the promotion of spontaneous apoptosis.8

It has been reported in the literature that certain plant compounds can inhibit virus replication.9 In the case presented here, the patient had previously received some of these first-line treatments, but without successful resolution of her warts. The patient presented with a chronic and severe case of verruca vulgaris, and she was subsequently treated with a topically applied botanical formulation. Within a month’s time of treatment, the patient’s warts were nearly resolved, demonstrating the efficacy of the botanical blend.

A 21-year-old female patient presented with a diagnosis of verruca vulgaris (common warts), with visible elevated and roughened lesions on the palm of the right hand. Photographs of the patient’s lesions were obtained upon initial intake (pretreatment), 3 weeks into treatment, 4 weeks into treatment, and 6 months following treatment. All images represent the palm of the right hand.

Before treatment, multiple lesions of various size covered approximately 20% of the patient’s palm (Figure 1). The largest lesion was 3.2 cm in length. The patient’s physical characteristics at intake are shown in Table 1.

The patient reported having the warts for 12-14 months. Prior to intake at our facility, she had received treatment from a dermatologist. This treatment involved cryotherapy with liquid nitrogen. It was unsuccessful and the warts returned. Subsequently, the patient was treated with cantharidin. This treatment resulted in the development of severe blisters and was a very painful experience for the patient. Following this treatment, the warts returned without any resolution of symptoms. The patient was subsequently scheduled for surgical excision of the warts. Not wanting to undertake the surgical procedure, she contacted our facility. The cantharidin treatment had occurred 2 months prior to our initial intake of the patient.

Upon intake, the patient had complaints of pain, erythema, and disfigurement to the right palm, coupled with the psychological stigma associated with the warts. The patient’s vital signs and medical history were taken, which did not affect the diagnosis or treatment plan. After a medically focused assessment, a botanical-based therapy was implemented. Many botanicals have proven antiviral and analgesic properties. A commercially available botanical gel containing Hypericum perforatum (2.5%), Lavandula officinalis (10%), Glycyrrhiza glabra (2.5%), Melissa officinalis at (6%), Eleutherococcus senticosus (4%), and Sarracenia (mixed species) (25%), suspended in a proprietary gel, was chosen due to the historical antiviral and analgesic properties associated with these botanicals. In addition, the gel formulation contained allantoin and glycerin, which are known to improve skin healing.10,11

Explicit instructions were given to the patient, including detailed application instructions. These included: a) wash the area with warm water only (no soap) and pat dry; b) beginning at the outer edge of the area, apply a very thin layer of the gel, then apply the gel to all remaining lesions uniformly; and c) cover the entire area with a Teflon-coated bandage. Reapply the gel QID, rewashing the area prior to bedtime and once again in the morning. Repeat the instructions for each application. The patient was asked to document any side effects or concerns.

After the first 2 weeks of treatment, the patient reported minor changes in symptoms, including a slight increase in redness surrounding the lesions (Figure 2). The patient reported an absence of any pain associated with the lesions within the first day after application of the gel.

Figure 2. Severity of Symptoms Over Time

Symptoms were ranked on a scale of 0-10 (10 being most severe). Assessed symptoms included the diameter and elevation of lesions, erythema, and pain. Symptoms were recorded during the initial intake, weekly visits, and follow-up visits.

During the third week of treatment, the roughness and elevation of the lesions were greatly diminished (Figure 2), but they remained erythematous (Figure 1).

At the 4-week mark, the lesions were substantially healed and were “leathery” in appearance (Figure 1). The erythema of the lesions diminished and appeared slightly pink in color. The patient reported no pain or any side effects during the entire treatment period. At this point it was decided to discontinue the use of the gel and proceed to monitor the patient for any reoccurrence.

At the patient’s 6-month follow-up, no warts or erythema was observed (Figure 1). At an 18-month follow-up, the patient remained asymptomatic.

This case supports the use of a topically applied botanical formulation as an efficacious and non-invasive treatment for verruca vulgaris. The botanical gel was selected due to the antiviral and analgesic properties historically associated with the ingredients. The botanicals present in the blend included Hypericum perforatum, Lavandula officinalis, Glycyrrhiza glabra, Melissa officinalis, Eleutherococcus senticosus and Sarracenia spp suspended in a gel. Hypericum perforatum has been shown in vitro to inhibit the transcription of the hepatitis B virus.12 Melissa officinalis has demonstrated inhibitory properties against herpes simplex viruses,13 and Glycyrrhiza glabra has shown in mouse models to have activity against the papilloma virus.14 The root of Eleutherococcus senticosus has shown antiviral activity against DNA viruses, including adenovirus and herpes simplex virus-1.15 Historically and in laboratory studies, Sarracenia purpurea has demonstrated activity against poxviruses.16

All of these aforementioned viruses have a similar feature of a DNA-based genome. Although none of these botanicals have substantial historical activity against HPV, the DNA genome structure of HPV may suggest the use of these botanicals against this virus family as well. In addition, the botanical Sarracenia has a long history of pain relief, as it has been used for centuries as an anesthetic17 and is currently marketed as a pharmaceutical analgesic.18 For the case presented here, the botanical formulation provided relief of symptoms, likely through the antiviral and analgesic properties associated with these botanicals.19

Current standard treatments of care for verruca vulgaris are commonly invasive, painful, and often unsuccessful.20 The use of this synergistic blend of botanicals in a gel base could prove to be a more efficacious treatment than the current standard of care. Current literature supports the use of traditional medicinal herbs in the treatment of viral infections.21 The efficacy observed in this case study supports the need for additional research of this botanical formulation, not only against HPV strains associated with common warts, but also for more severe HPV strains, including HPV-6 and 11, and HPV-16 and 18, which lead to genital warts and cervical cancer, respectively. Further investigation into novel uses of botanical extracts, as well as their polypharmaceutical interactions, should be encouraged21 in order to provide patients with efficacious and non-invasive alternatives to current HPV treatments.

Vanessa Ferreira, ND, is a naturopathic physician from SCNM, where she completed this case study as a student. During her naturopathic education, Dr Ferreira focused her time on Global Health, Women’s Health, and Homeopathy. In addition, she has extensive experience as a teaching and research assistant at SCNM. Her main research project – on inhibiting Candida growth and differentiation with the use of botanicals – was showcased at the AANP in 2014. Dr Ferreira has worked in the Biodesign Institute at Arizona State University, doing research on botanicals and herpes viruses. She looks forward to providing more case-based research to support the efficacy of modalities used in naturopathic medicine in the future.

Vanessa Ferreira, ND, is a naturopathic physician from SCNM, where she completed this case study as a student. During her naturopathic education, Dr Ferreira focused her time on Global Health, Women’s Health, and Homeopathy. In addition, she has extensive experience as a teaching and research assistant at SCNM. Her main research project – on inhibiting Candida growth and differentiation with the use of botanicals – was showcased at the AANP in 2014. Dr Ferreira has worked in the Biodesign Institute at Arizona State University, doing research on botanicals and herpes viruses. She looks forward to providing more case-based research to support the efficacy of modalities used in naturopathic medicine in the future.

Author Affiliations:

1Southwest College of Naturopathic Medicine, Tempe, AZ 85282; 2Arizona State University, Biodesign Institute, Tempe, AZ 85287; 3Precision Surgical, LLC, Scottsdale, AZ 85260; 4Total Wellness Medical Center/Vital Force Naturopathic Compounding, Surprise, AZ 85374

References

It is a long established fact that a reader will be distracted by the readable content of a page when looking at its layout. The point of using Lorem Ipsum is that it has a more-or-less normal distribution of letters, as opposed to using ‘Content here, content here’, making it look like readable English. Many desktop publishing packages and web page editors now use Lorem Ipsum as their default model text, and a search for ‘lorem ipsum’ will uncover many web sites still in their infancy.

It is a long established fact that a reader will be distracted by the readable content of a page when looking at its layout. The point of using Lorem Ipsum is that it has a more-or-less normal distribution of letters, as opposed to using ‘Content here, content here’, making it look like readable English. Many desktop publishing packages and web page editors now use Lorem Ipsum as their default model text, and a search for ‘lorem ipsum’ will uncover many web sites still in their infancy.

The point of using Lorem Ipsum is that it has a more-or-less normal distribution of letters, as opposed to using ‘Content here, content here’, making

The point of using Lorem Ipsum is that it has a more-or-less normal distribution of letters, as opposed to using ‘Content here, content here’, making it look like readable English. Many desktop publishing packages and web page editors now use Lorem Ipsum as their default model text, and a search for ‘lorem ipsum’ will uncover many web sites still in their infancy.

It is a long established fact that a reader will be distracted by the readable content of a page when looking at its layout. The point of using Lorem Ipsum is that it has a more-or-less normal distribution

Copyright BlazeThemes. 2023